It was well after midnight when I drove down the rural lane leading to the familiar house deep in a "holler" in Northeast Tennessee and pulled into the driveway. As I entered the house, I was greeted with the must and staleness of a house that has sat dormant for way too long. Mice have made themselves at home in cabinets and crevices. The house has no air conditioning, and the humid summer has exacerbated the unpleasant smells. Even so, I dragged my stuff in from the rental car, climbed the stairs, spread my travel blanket on the bare mattress in the guest room and crashed. I was exhausted, having completed more than 1,700 miles of driving over two long days and stopping at the Abingdon hospital to check on the reason for this journey -- my mother.

My mother's story deserves a book -- an epic one at that. The last seven and a half years have been a story unlike any I thought I'd be part of, with the last 22 months being nothing short of surreal. I often think this story would sell better as fiction because so many parts of it are unbelievable -- even to me, and I've lived them.

|

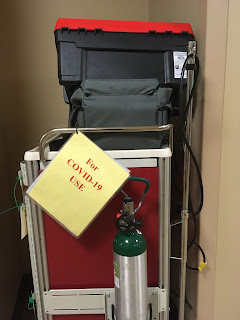

Each hospital floor has a COVID cart.

|

But for now, I write about the present. This is a COVID story after all. I traveled alone across the country to say goodbye to a woman with whom I have had a rocky relationship from my time in the womb. My brother is mired in the economic trauma brought about by the pandemic, my daughter has just started her first year of college online, and my partner is minding the homestead and tending to our COVID puppy and aging feline. And honestly, this is a brutal and risky trip. So I travel alone to say goodbye. At least I think I'm saying goodbye.

When I spent Saturday morning on the phone with a myriad of my mom's caregivers at the hospital they weren't sure she would even be around by the time I reached the hospital. When I checked in with the palliative care doctor while en route, she expressed surprise at how well my mother was doing. So when I entered my mother's room at the hospital, I actually wasn't surprised to see her watching yet another episode of "Bonanza."

Since November 2018, I have sworn to never bet against that woman.

Back then, we received a call that she was in hospital-based hospice, and she had mere hours left in this life. My brother and his family flew out on Thanksgiving; I followed the next day. We were greeted with a comatose woman who was completely unaware of our presence and hours from her demise. I'll save the nitty gritty details -- really, it's a book -- but clearly, that was not the end of my mother's story.

Fast forward to this week. Her dear friend, Walter, and I are tag teaming our time with mom. I know how fortunate we are to have this time. If she were at her nursing home, neither one of us could visit. Given that she is on "comfort care," we are both allowed to visit. In this COVID world, many folks in their last days do not get the gift of loved ones at their sides. In talking with the medical team, that seems to weigh on them heavily.

On Monday night, when I first visited her at the hospital, I vacillated between staying and driving the final 30 minutes to her home so I could sleep. It dawned on me that this woman has not had visitors since my daughter and I visited her in January. I could easily afford to spend a couple more hours simply holding her hand.

On Tuesday, the palliative care team and I discussed our options given mom's stable condition. In normal instances, they could just send her to hospice at her nursing home. However, that would mean that she would not only be alone and unable to have us visit, but she would also be completely quarantined for two weeks since she has been in a hospital. The med team agreed to prolong her stay at the hospital for as long as possible.

On Wednesday, I walked into a different story. I heard her as I stepped off the elevator, and I walked into a room full of nurses and nursing students. "Bonanza" was still on the TV, but one look at my mother, and I knew that whatever progress she had made over the past two days was gone.

There is a voice in the back of my head reminding me that I shouldn't bet against this tenacious woman, but...

She uttered at some point yesterday that she was done. On "comfort care," there is no more poking and prodding. Just drugs. Morphine, specifically. And today it started flowing regularly. It eases her pain, but it doesn't eliminate it completely. She spent the day flitting between unconsciousness and agony. She still responds weakly to visitors -- whether in person or on video, but her eyes tell me that she grows weary of this life. Unfortunately, there is nothing I can do to modify this process, but I have promised that I will be by her side for this last stage of her journey.